David Barnard started developing apps soon after the first iPhone was released. In the last 12 years, he has seen each minor and major change play out in the appstores – from the first paid apps and their price drops – to the explosion of freemium – to the advent of subscriptions. In today’s episode, he tells the stories of living through the roller coaster that the appstore has been.

If you’re wondering as to what relevance details from a decade ago will have to our world today, this episode will help you think about the unseen forces that influence what we see on our phones, and about how Apple’s policies have influenced the kinds of apps that flourish. Just as important, all of this helps contextualize the looming privacy changes that will effectively deprecate the IDFA in iOS 14.

This episode provides a fascinating and in-depth look at how the last decade helps us learn about what’s ahead – and we’re excited to present it.

ABOUT DAVID: LinkedIn | Website | Twitter | RevenueCat | SubClub HQ

ABOUT ROCKETSHIP HQ: Website | LinkedIn | Twitter | YouTube

KEY HIGHLIGHTS

💼 David’s background

2️⃣ 2 primary reasons why the App Store was a game-changer in 2008-09

🛡️ Introducing the App Store: a platform consumers trusted

🧶 App Store enabled indie developers

💸 Price played a huge role in galvanising the App Store

🗿 The Stone Age of monetisation

💰 Why the only way to earn from an app was to have a paid app

🤑 What “free apps are free” meant for monetisation

🍎 How the smallest of Apple’s decisions shaped the app marketplace

📊 The tale of 2 top charts

📸 Exposure: How curation influenced market economics

📲 Limited monetisation led to mass market apps

✨ With subscription, you get sophistication

⛔ The limited scope of early ad-monetisation

🎮 Games were big winners

⌛ The timeline of how the platform and the marketplace evolved together

🆓 The advent of in-app purchases – and the freemium/free-to-play model

🥕 Subscriptions and in-app purchases changed the incentives for developers

♾️ Value is the biggest driver of the subscription economy

🧯 Apple’s new IDFA policy is to offset some of the ills of the monetisation models

⚠️ Freemium isn’t evil; but it brought about unintended consequences

🔜 The future of the app economy is value-driven subscriptions

💞 How Tinder is an example of a subscription that also has consumable purchases

KEY QUOTES

There was no freemium in the beginning

“So Steve Jobs said, famously, free apps are free. And so there were no in-app purchases allowed. He was like: “We don’t want our customers to be tricked: downloading a free app, and having to then pay. So free apps for free.” You can monetize via ads if you want. But free apps are free. And paid apps are paid. And that was it.”

How Apple’s chart design influenced app pricing

“It didn’t matter if your price was $30, and you got 1000 downloads, or your price was $1, and you got 1000 downloads. Whoever had the most downloads showed up the highest in the charts. That to me is just the perfect example of how the market wasn’t free and that Apple heavily shaped the market through those seemingly inconsequential decisions.”

David’s early attempts at marketing apps

“I would do experiments with paid marketing. I did one where I paid a $30 CPM to Macworld magazine. And I forget exactly how much I spent, but it was I think it was a grand or two and it drove like $100 in revenue. Because being paid upfront with no free trials, no way for people to get a sense of the quality of the app before ponying up the money—doing paid advertising on a paid app? Well, the numbers just didn’t work.”

The downside of data ubiquity

“Well, there’s a tonne of companies operating in the shadows that have developers installing these SDKs that are building these shadow profiles on people. You have no idea who they are; you have no idea what data they have. And if they’re installed in multiple apps on your phone, there’s so much that they can triangulate about you and your behaviours and your location and everything else.”

Why apps like Flighty are enabled by the subscription model

“Another great example is Flighty. It’s a friend of mine who built that app. It’s a flight tracking app, and it is phenomenal. And he couldn’t have built that without a subscription model. His data costs are insane, because flight data is really expensive. But because of the subscription model, he was able to build an incredible tool for people who are flying all the time.”

How an app can have subscriptions & consumables

“And what’s really fascinating to me about Tinder is that, not only are they using the subscription model, but they have consumable purchases in there. I think we’re also at the beginning stages of subscription apps figuring out how to better monetize the true fans, who would excitedly spend hundreds of dollars a year in the app, not just a $20 a year subscription. And I think we’re going to see that more and more. And you’ve already seen that shift in the last probably 5-10 years.”

FULL TRANSCRIPT BELOWShamanth: I’m very excited to welcome David Barnard to the Mobile User Acquisition Show. David, welcome to the show.

David: Thanks. Thanks for having me.

Shamanth: David, I’m thrilled to have you. Certainly, I’ve been wanting to have you on the show for a long time, partly because you’re the real deal.

You’ve seen so much of how the App Store ecosystem has evolved since the earliest days. And you haven’t just been an armchair expert, you have been a developer yourself. You have been an indie developer since 2008. And what’s crazy is I go back and look at some of your writing since 2008 and 2009; so much of what you wrote, even back then, is very prescient. Certainly, we’ll touch upon a lot of what you wrote, and how monetization of the App Store has evolved over the years.

But perhaps a good place to start would be for you to share your background, which I also find it intriguing because you were not an experienced developer; you were not a designer; you were not even like a programming hobbyist, when you launched your first app.

Something we found in the course of our research, was your photograph on the front page of the San Antonio Express News, with a caption that said: “David Barnard reacts with joy…” So, tell us your story. What inspired you to start developing apps and why that photograph is relevant to what we’re talking about?

David: Sure. Okay, well, I’ll see if I can condense it, because it is a long story that starts 14 years ago.

I was a recording engineer, and actually studied that at a university. And as a recording engineer, I ended up switching to the Mac platform and got a powerbook back in the day, which got me into Apple’s ecosystem. And so when the iPhone was announced, I was pretty excited. I was a pretty big Apple fanboy back then. And so I was going to pick it up at some point, in the first few days.

And then my brother calls me: “Hey, let’s go wait in line. Let’s meet in San Antonio, wait in line and make sure that we can get an iPhone on day one: I was like: “Okay, that sounds like fun.” And so we headed down to San Antonio, we stayed up all night. It was this nerdy group of people camping out in the parking lot. And I was the first one in San Antonio to get an iPhone. I ended up being first in line because we just happened to get to the parking lot at just the right time.

That was 2007. I was working as a freelance recording engineer. I got married that fall, and realised that it was not a good job to raise a family and be married. I was working from 2 in the afternoon till 2 in the morning, my wife was working 9 to 5, and I never saw her.

I’ve always been pretty entrepreneurial. I started seeing rumours that Apple was going to announce an SDK. So I started coming up with ideas, writing a business plan, and thinking about all that. And so I actually founded my company days after Steve Jobs announced the original iPhone SDK.

I intended to do the programming myself. But as you noted, I had zero experience. And so I got about two weeks into one of the programming books, while simultaneously talking with lawyers about incorporation papers, and all that kind of stuff. I realised that I wasn’t going to be able to build a business, and learn to code, and ship a good app day one. So I started working with contract developers, and have ever since; a combination of contract developers and I’ve also partnered with some developers on apps.

And so from 2008, I’ve shipped 20 apps now. And I’ve sold three of them, so I’ve had three exits. I think I’ve had an app hit number one Top Paid; Launch Center Pro hit number one Top Paid. My Mirror app—it was a total fluke—had millions and millions of downloads.

Over the course of the 12 years, I’ve been doing this, I’ve seen millions and millions of downloads, and millions and millions of dollars of revenue. So yeah, I’ve been around the block.

Shamanth: And you’ve done it yourself, right? You’ve done things hands-on.

David: Yeah, never hired an employee It’s all just been me, and then a mishmash of contractors and friends and partners and collaborators and whatnot.

Shamanth: Yeah. And you’ve seen from close up, how much of a game changer the iTunes store was. Not just that, you hitched your wagon to the iTunes Store; you started your own thing at that at the time, before the mass market potential became very clear to everybody. Certainly, there’s many aspects of the evolution that you’ve seen over the last decade or so that I want to dig into.

Something that I think would be a good place to kick this off would be to get some idea and understanding of why iTunes store was such a big game changer. It’s my understanding that one of the big changes that the iTunes store made was to make sure that buying software became so much cheaper. Prior to that, you had to go to a store, buy software for hundreds of dollars. Software could be games; you could buy games for hundreds of dollars. This became so much cheaper.

Would you agree that the price of software—could be games, could be apps like yours—becoming so much cheaper was a big reason for the explosion? Or what else would you attribute the explosion of the App Store to, at the time?

David: Yeah, this is something I’ve talked a lot about over the years and could probably talk about for an hour, just this one topic, unpacking the history of monetization, even in the first year or two of the App Store. I blogged about it, and John Gruber linked to my post and I started meeting a lot of fellow developers through Twitter.

So I had a front row seat to all this; made tonnes of friends who had some of the top apps on the app store in those early days. My apps did really well in those early days. A lot of people who talk about 2008-2009 and talk about that part of history, they didn’t have skin in the game; they didn’t have an app on the App Store. They’re theorising about this economic situation from visions of the past, not from having lived through it.

So the App Store was a game changer in many ways. Apple, famously with their antitrust suits going on right now, has said that they were the first internet distribution. And you were talking about, you know, physical distribution of software. By that time in 2008, there was already a Palm Pilot store that you could download apps directly to your Palm Pilot. Software distribution online was already very popular.

But what changed with the App Store—and I think was really fundamental to the success of the App Store—was a combination of a few things:

1) The iPhone platform itself: multi-touch, personal computing was just such a game changer. The entire interaction model of an iPhone was just so game-changing to how humans interact with computers. And not just any computer, a computer in your pocket. And that was just such a fundamental game changer. Honestly, I think that is really the primary driver. If people had been able to sell software on their own websites, I think we still would have seen a huge boom of software.

2) The App Store did bring a ton of value, especially for small developers like me, where I didn’t have to set up a payment provider. I didn’t have to worry about collecting and distributing taxes. I didn’t have to worry about setting up a server to distribute the software. I didn’t have to think about all these things. People talking about it now, they’re like: “Oh, yeah, you just use Stripe; AWS is great; you could just set up a Linode in 5 minutes!” Back in 2008, it wasn’t quite as seamless. There weren’t all these super easy APIs. I don’t know if GitHub even existed in 2008. We were using SVM and other more primitive technology.

So I think the App Store brought a tremendous amount of value in being a trusted place for consumers that they knew they could go there. They knew Apple was approving the apps, Apple already had their credit card, they didn’t have to go buy each piece of software individually and type in their credit card each time. It downloaded right to the device.

Apple did provide great curation. Most people thought that the App Store editorial page, early on, was just randomly generated by an algorithm because it didn’t have the kind of human touch that we see now in the editorial pages with stories. But there were humans behind that picking the apps and helping to curate. So I do think that the App Store itself was a huge part of that. But again, I still say primarily it was just the platform itself.

Then stepping down another level, price did make a difference. Early on, you had millions of people who had paid $699, unsubsidised, which was crazy at the time. There’s a famous Steve Ballmer video of him laughing and saying: “Who’s going to pay $699 for a phone, unsubsidised?” And clearly he was wrong.

The iPhone platform was already heavily skewed toward higher income individuals, with a propensity to spend on technology, who probably were more—I wouldn’t say nerdy, because my dad got an iPhone and he’s not nerdy at all. But there was definitely a higher propensity to spend and care about technology, and care about the platform in those early days. So I think price was certainly partially a factor that you went from Palm Pilot, where a lot of the apps were $30 or more, to the iPhone, even in the very early days, a lot of the apps were $10, $15, $20. Nobody knew how to price. But as I guess we’ll talk about that; that did quickly devolve.

I’d say really the platform is what made it, and then the App Store was a secondary thing.

Shamanth: Certainly. And that seems like such a huge change for somebody today that’s around a lot of free apps didn’t know that apps cost $10 to $20, which can feel like a lot just now. But it’s my understanding that, at the very beginning, you just had paid apps. Is that accurate? Is that accurate to characterise?

David: It’s so fascinating to look back and think about how the entire app store was framed from those early days that today, we just think is bonkers.

So Steve Jobs said, famously, free apps are free. And so there were no in-app purchases allowed. He was like: “We don’t want our customers to be tricked: downloading a free app, and having to then pay. So free apps for free.” You can monetize via ads if you want. But free apps are free. And paid apps are paid. And that was it.

There were no in-app purchases for 2-3 years. If you wanted to make money, you either displayed ads, and again: “Yeah, just drop AdMob in your app; drop Facebook Audience Network in your app; and you’ll make plenty of money.” This is 2008, AdMob was started right around that time, and I think launched pretty soon afterward. But it was all so primitive; there was no guarantee you could just drop in an ad network and make it work. Flurry started around that time. It was all just coming together.

And so, there were ad-supported apps, and that started to take off and grow pretty quickly. But if you really wanted to make money directly from your customers, the only option was to have a paid app. And that certainly shaped the market tremendously from those early days. The first few years, with no in-app purchase, no ability to do freemium, the early days of the App Store, you charge for your app. And that was the way you made money.

Shamanth: How did that shape the App Store and the kinds of apps that were out there at the time?

David: There’s a lot of things that contributed to the early shape of the market.

One of the biggest things in my mind was the shape of the App Store itself. And this is something, again, I could talk for 30 minutes just on the economic principles behind the shape of a market influencing the products that are then delivered in that marketplace.

And so, Apple, with every little decision they made on how they App Store worked: what apps they approved and didn’t approve; how they ran the top list; how they promoted apps within the store. Every little decision they made shaped the market in a specific way that then influenced the pricing, influenced the apps that were made, influenced what apps did well, and what apps didn’t do well.

So Apple heavily shaped that market. And I wrote a post in 2009, saying the App Store is not a free market, because you had all these people saying: “Oh, the App Store is just a marketplace like any other. There’s going to be competition; prices are going to trend downward as competition increases.” All that sort of thing.

But I think that really misses just how much influence Apple had over the App Store, especially in those early days. I think they’ve lost some of that control over the years, with Facebook and Google Ads being a higher proportion of downloads a lot of times than some of their efforts for curation and whatnot.

Honestly, one of the biggest influences early on was that Apple had two top charts. They had Top Free apps, and they had Top Paid apps. And the Top Paid apps were sorted by download volume, solely.

It didn’t matter if your price was $30, and you got 1000 downloads, or your price was $1, and you got 1000 downloads. Whoever had the most downloads showed up the highest in the charts. That to me is just the perfect example of how the market wasn’t free and that Apple heavily shaped the market through those seemingly inconsequential decisions.

Seems normal: “Oh top charts! Top Free is top downloaded free and the Top Paid is the top downloaded paid.” But what quickly happened was that developers realised: “Well, if I have my app priced at $5, and I’m only getting 1000 downloads at $5 I’m making $5,000 a day. If I dropped my price to 99 cents, I get 5000 downloads a day and make the same $5,000. But I’m going to show up higher in the charts.” And then guess what happens when an app is high on the charts? Oh, it must be a good app, people are downloading it. So the charts carried a bit of social proof with them. And so the higher you get up in the charts, it actually was its own form of marketing, in that you would get additional organic installs just from showing up on the chart.

You have all these onlookers who are like: “Oh, no, that that was just normal market pressure. Prices just drop in a competitive market.” But those people didn’t have apps in the store making those decisions personally. I played the game, right? I put my app on sale, and I saw the downloads skyrocket. And then I had friends who played the game and their app skyrocketed. It was a 99 cent app, and it skyrocketed to number one. And once it hit number one, it stayed at number one for weeks and weeks and weeks. So even at 99 cents, they were making maybe tens of thousands of dollars a week, because the marketplace was still relatively small.

You weren’t making like hundreds of thousands of dollars a day at 99 cents, even at the top of the chart. But for those of us who had that front row seat, we could just see, plain as day, that the incentive for dropping the price was the charts, it was exposure. And then a lot of sites came along that, if you dropped your price, there were newsletters like: “Price drops” or “Get the apps while they’re on sale.” And so in the early days, we were playing that game all the time; dropping prices to put the app on sale. And there were times I’d make $10-$15,000 in a day, just by dropping the price a couple of bucks, and then raising the price back up.

That kind of thing is a more natural market pressure; stores do this all the time. Black Friday is a great example. So those are more natural market forces. But when you drop your price specifically to show up high in the charts, which then garners more attention; that’s how the game started and evolved from there.

Nobody would care to read it, but there could be whole books, economic white papers written on some of the market dynamics that were happening in those early days.

Shamanth: Certainly. The way you describe it, every single micro decision that Apple made around how it structured the App Store, basically dictated all these behaviours that, as you said, would incentivize the developers to drop their prices. They were like: “Well, this is the incentive scheme that Apple is going to set up.” The lower your price goes, the more money you make, which can still be a fortune for an independent developer, or a small developer, with even thousands of dollars which is fascinating. Like you said, every micro decision, and I can’t imagine it wasn’t intentional, because they could see the consequences of their design choices.

David: And I forgot to finish answering your question, because again, I could talk about that question for an hour easily. But the thrust of your question, though, is how did it impact what kind of apps were made? That is actually a really important thing to address, especially for indies but even for some of the bigger companies.

When you saw those market dynamics, it was really hard to build a sophisticated app, and come to the market at $30 or $40. And since we couldn’t do any kind of subscription, or multiple in-app purchases, or any other way to monetize those users, other than ads or a paid app, you did see the market shift toward the kind of apps that could go more mass market versus more sophisticated tools.

I think that’s where we’re seeing a huge shift today with the subscription model. It is that because you’re able to charge higher prices and have that income be recurring, we’re seeing much more sophisticated apps being built today, even in smaller niches of the App Store, because it can support that.

Early on, even with my $5 apps, I did experimentation with marketing. We didn’t have Facebook-level targeting, where you could find business owners and direct them towards my mileage log app. So maybe it could have been more successful back then with that kind of targeting.

I would do experiments with paid marketing. I did one where I paid a $30 CPM to Macworld magazine. And I forget exactly how much I spent, but it was I think it was a grand or two and it drove like $100 in revenue. Because being paid upfront with no free trials, no way for people to get a sense of the quality of the app before ponying up the money—doing paid advertising on a paid app? Well, the numbers just didn’t work.

And, again, this was the Dark Ages—zero way to track installs from an ad, it was just back-of-the-envelope, incrementality testing. You would do a marketing campaign and you would watch for lift then; any organic lift, or if you happen to get a press mention, or you happen to update the app. In the early days, it was hard to make any kind of concrete determination about how your ad spend was affecting revenue.

But even then, any marketing I did was so clearly ineffective. At some point, 2009, AdMob gave developers something like $4,000-$5,000 of free ads, if you just signed up for their platform, because they just had so much inventory, and were burning the VC cash to get market share, which is smart. They got bought by Google for millions or maybe hundreds of millions. Yeah, Google bought them pretty early. I did $5,000 in marketing with AdMob and the return on that 5000 was miniscule. I saw just hundreds of dollars lift on thousands of dollars of ad spend.

So, not being able to charge more, not being able to more effectively do paid marketing—it did really shape what was built. It shaped the kind of developers who came to the market. There were apps like Evernote; a great example which was a VC-backed business. You could subscribe on the web, and the app itself was free on the App Store.

Apple did allow those sorts of apps that had a subscription online or some online payment still to this day, somewhat like business exclusion or the reader app exclusion. It’s like, if Evernote had a certain amount of functionality, standalone, for free on the App Store, then Evernote could charge their subscription online. But those were few and far between, in those early days, there weren’t a lot of those kinds of businesses built. Those that were built were incredibly visionary compared to us indies, just kept scrapping it out, trying to get a hit app and trying to get mass market success.

There were so many factors in play in those early days, with the way Apple did things, with just the incredibly limited tooling we had for things like measuring ad spend, the limited analytics that we had—although Flurry ramped up pretty quickly. And there were a couple of other companies early on that tried to do things. Looking from hindsight from 2020, they were so crude compared to the kind of tools that we have today.

So it was fun, though; it was such a nascent industry. You just didn’t know what was going to work and what wasn’t. There was a lot of experimentation. It was certainly a fun time to be building apps.

Shamanth: Certainly. It also sounds to me, at the time, the way the app store was designed and constructed, it wasn’t amenable to building sophisticated apps, relatively complex apps, or relatively niche apps, as you expressed. So, at what point did it become clear that this could support big businesses, hundreds or millions dollar businesses? Did you feel like there was a point when that became clear, either in Apple’s decisioning and choices, or the entry of larger gaming developers, larger developers? I’m wondering if there was any point when you saw maybe there was a switch that was flipped?

David: That’s a really interesting question because, in some ways, early on, I think there was an over optimistic view that then proved to not pan out, as big as was expected at the time.

For example, Kleiner Perkins had a 100-million dollar fund to fund apps. I believe they announced it with the SDK, in March of 2008. If I had thought of this before the show, I would have gone and researched to see what investments they made and how those panned out. But my guess is that that fund did not perform especially well, unless maybe they did stumble upon one big hit. Maybe they invested in Evernote, which has struggled as of late, but did grow to near unicorn—or maybe unicorn status—at some point.

So early on, there was a lot of optimism around the potential of the platform. And then, in part because of those dynamics, it does seem like there were few years where there weren’t as many kinds of big ambitious projects launched, or some of the big ambitious projects that were launched flamed out pretty quickly.

Games were the early big winners; it was really obvious that games were making great money both as paid—or especially as paid. But then some of the freemium ad-supported games started to do well. This is a brief overview of the history of monetization on the platform. Apple did enable in-app purchase in, I believe it was, 2010. And that’s when you really started to see the rise of freemium games.

It was 2010 to 2011, when they announced the in-app purchases. And so, there was this two-year period that was somewhat stunted, but it also aligns with the growth of the iPhone itself. Because, early on, when they launched the App Store, they were single digit millions of people who had an iPhone. And then by 2009, they were hitting double digit, millions of people who owned an iPhone. And then by 2010, when they announced in-app purchases, there were tens of millions of people who owned an iPhone. Underlying some of these market dynamics that were in play in those early years was also just the incredible growth of the platform itself.

Then in 2010-ish, they announced in-app purchases, and so then you could at least start experimenting with true freemium models. Back in the early days, we did do lite apps that were free, and then tried to push people to pay. So there was some level of freemium experimentation going on, but it was a very poor substitute for real freemium.

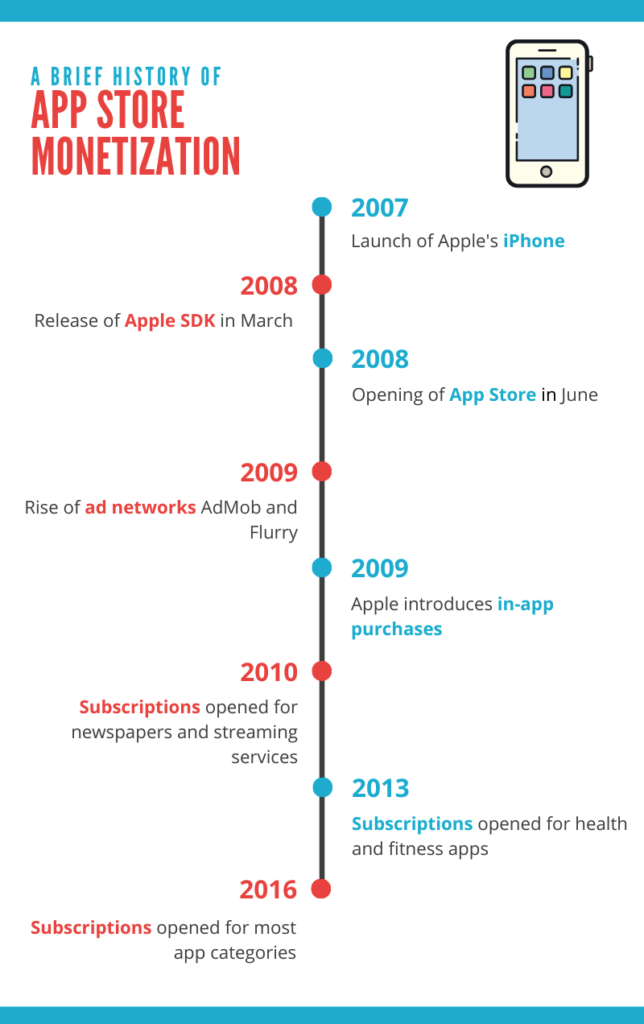

We’ve seen the platform grow tremendously over the last 12 years. But I think the two big milestones for monetization were the addition of in-app purchases, and then Apple opening up subscriptions. So early on, around 2010, when they launched the iPad, they allowed newspapers, Netflix and people like that to use subscriptions. Then in 2013, they started opening it more to health and fitness apps and other things that made sense for subscriptions. And then in 2016, they opened the doors a little more widely for subscription monetization.

I think that that combination of freemium and the subscription business model is what’s helped propel the App Store to where it is today, where we are starting to see so many very sophisticated, very big companies built around mobile. That’s kind of our thesis at RevenueCat—we hadn’t really talked about that; I did join RevenueCat and it’s partly because of my bullishness around where things are headed.

But what we’re seeing is mobile-first companies using the subscription business model to grow into unicorns. You have Calm and Headspace. And then Lighttricks, famously was one of the early ones that first raised at a billion dollar valuation, and they’re selling a subscription to a selfie editing app. It still blows my mind that people are willing to pay for that.

And so now it’s really fun as a developer advocate at RevenueCat. I am constantly talking to developers and get to see these really fun niche apps that people are building because the subscription model allows them to monetize. Yeah, we have an indie developer building an app for knitters—I think it’s called Yarn Buddy—which is super cool. Who would ever bother building for such a small niche; and it’ll probably never be a huge business. But those are the kind of niches that could support an indie developer full time. I spoke to a developer of an orienteering app yesterday, which is fascinating. It’s a small niche; it’s not going to support a VC-backed company, but he can carve out a really nice business there. So yeah, freemium starting in 2010 really started to change things. And then it really accelerated with the subscription model.

And again, people forget all the little rules and nitpicky things that Apple’s done over the years. They’ve been really picky about any kind of free trial. And then finally, you can do free trials, if you use Apple’s subscription free trial, and they’ve been picky about doing any free trial that doesn’t use their subscriptions. So all those things continue to shape what’s built and how we build them. Not to mention all the little nitpicky App Review things about using frameworks for their intended purpose, instead of building more innovative stuff that pushes the boundaries. There’s just so much that has transpired over the last 12 years as we’ve come to this point.

Shamanth: Yeah. What I’m also taking away is that the two big inflections were: A) the advent of freemium; and B) the ascendance of subscriptions. Again, I’m fascinated by how these policies influenced the kinds of apps that really took off. You touched on how the subscription model taking off has influenced the sustainability of more niche products. And, certainly, I think you’ve talked about how the freemium economy really led to that ascendance of the entirety of the app ecosystem.

I’m curious, with iOS 14 coming in, are there certain aspects of this dynamic that Apple is trying to reverse that could be because of what’s happened over the last decade or so? How are you looking at iOS 14? And the impact of freemium and subscription models that may or may not have been intended consequences of these policy changes?

David: Yeah, that’s a great question. There’s smaller micro economic and larger macro economic impacts of these things. So, for example, I think the switch to freemium, in addition to kind of opening up the in-app purchase business model, opened up the app store to some of the darker motivations of those.

So a free weather app, for example, monetizing via ads, could also sell their user location data. The incentive there was to get as many people using the app as you possibly could, because the location data was so much more valuable than trying to charge people what they were used to paying for apps.

The Weather Channel is a fantastic example; IBM bought them. And I don’t know if this is really true or not, but I can’t help but believe that one of the primary motivations behind IBM buying The Weather Channel was the treasure trove of location data. IBM does a lot of consulting—I imagine even have defence contracts and things like that. And so here you have the most popular weather app in the US, with just a treasure trove of real time location information, and even background location information. Because with a weather app, you might want to know if a tornado alert comes in. And so you turn on ‘Always on’ location, and multiple times a day—sometimes multiple times an hour—your precise location is being uploaded to their server. And you’re essentially able to be tracked 24/7. And I can imagine that one of the primary motivations for IBM buying that business was to have that data to power so much of their other consulting and other businesses.

Those sorts of things and privacy-related stuff that’s gotten really dicey with freemium apps over the years, is what’s motivating Apple to make some of these big changes, for example, with the IDFA.

There’s two primary ways that The Weather Channel can track you individually—as you move around the city, country, whatever—is that they would need to upload your IDFA, every time that they also collect that location information. And they do and they did, and they have. I have a weather app and companies came to me, and were offering to pay me monthly based on the number of users I had, if I would insert their SDK to continually hit their S3 bucket with data from my users. So those things are what have pushed Apple to limit the ability to do that level of tracking.

The Weather Channel can also do it on IP addresses, but that’s much more fuzzy, much harder to fingerprint and really track one individual user. Although they can track your home IP addresses don’t change these days. And so when I’m at home, using the internet, I realise even with Apple’s tracking prevention that I’m the only iPhone 11 Pro that shows up at my IP address. So any app, any website that’s able to determine my screen size and IP address has a pretty good idea who I am.

There’s been a lot of theories around Apple wanting to regain control of the app install, where Google and Facebook do have a lot of sway in the iPhone market because they drive such a high volume of the installs and are able to capture so much revenue with their app install business. And so Apple limiting access to the IDFA in iOS 14—which they have postponed but it’s still coming—is partially a reaction to that.

Personally, I think the primary motivation is to regain control of the privacy side of things to limit apps’ ability to collect and collate these vast amounts of data on users and build these shadow profiles that are being built on people in the background that they have no idea of.

Personally, I’m a lot less worried privacy-wise about Google and Facebook, and some of these bigger companies. I can go to Facebook and delete the data they have; I can turn off certain tracking. They at least give you those tools, and you at least know when you’re using the Facebook app, that there’s some level of tracking that they’re doing. That’s kind of generally understood among consumers that Facebook has a lot of data on you.

Well, there’s a tonne of companies operating in the shadows that have developers installing these SDKs that are building these shadow profiles on people. You have no idea who they are; you have no idea what data they have. And if they’re installed in multiple apps on your phone, there’s so much that they can triangulate about you and your behaviours and your location and everything else.

And so I think Apple is bringing the hammer down on that and I think that’s the primary motivation is to start limiting that kind of extensive tracking of its users. And I think it’s genuinely, genuinely a good thing for humanity that random companies you’ve never heard of are not going to be able to continue tracking us the way they have been.

But it has other consequences. In 3-4 months, they’re going to fully enact the rules that were announced around iOS 14, and then we’ll see it play out over the next 9-18 months how it really impacts the App Store economy. It is going to be a huge shift. And I think there’s a lot of unknowns.

You have a lot of companies out there: MMPs and others very boldly claiming they know how it’s going to play out and boldly claiming that their tracking solutions are going to be okay. And I don’t think that’s the case. And I think Apple is going to be watching all of this very closely and potentially banning certain SDKs that aren’t following the rules; whether the spirit of the rules or the letter of the rules.

This is a next phase shift for the entire mobile app economy: in that it’s going to incentivize new things; it’s going to change the way people do business; it’s going to limit the effectiveness of targeted advertising; it’s going to limit our ability to measure the effectiveness.

But new tools are already being built: new ways of advertising, new ways of targeting, new ways of measuring, new ways of understanding are going to be built. Especially for developers like me, this is somewhat going to be a return to the fundamentals. It’ll somewhat shift back toward who can build the best product and retain their users.

I’ve seen a lot of apps come up over the last few years, speaking of motivations, if you can charge $10 a week and trick enough people into subscribing—Facebook can get really good at targeting those users who are going to forget to turn off or cancel their subscription. There’s a lot of businesses that have been built on those economics, with those kinds of motivations. This is going to be somewhat a reset of some of those incentives by making it harder to more directly target those users, making it harder to more directly measure the results and feed Facebook’s algorithms. So the apps that are going to succeed in this new paradigm need to get back to the basics, like product and retention.

I think for all the talk about efficiency going down and stuff like that; some of the efficiency and measurement has just been an illusion. So if you’re building a great product and you’re going to find ways to effectively and cost effectively market that. I think some of the apps who don’t have a great product are hopefully going to struggle in this new paradigm more than the apps that do.

Shamanth: Certainly. And what I do find fascinating about everything you said is that the roots of what is unfolding now lie in how the free-to-play economy came into being. Because I think free-to-play and freemium weren’t a problem in and of themselves, but they engendered a set of incentives. That basically was like, as you pointed out, The Weather Channel could sell it location data to monetize.

If it was purely ad-supported, it would have been much, much harder, or there wouldn’t have been nearly as many incentives; or if it was purely paid, there wouldn’t have been nearly as many incentives. But having the free-to-play model eventually led to hyper-targeting of users, and led to the IDFA being as powerful and as critical as it is today. And certainly that led to problems that I don’t think Apple envisioned at the time. And I think that led to problems that the developers didn’t see as problems, because we’ve all been weaned on it.

I’ve talked to web people who have done advertising on an app. They were amazed and surprised and shocked at the amount of personal data that mobile app marketers tend to have. So I think we all took that for granted to a certain extent. And what I’m taking away from everything is that, David, there were unintended consequences of these monetization choices that Apple made. And I think certainly shifting to subscriptions, had curbed some of these to a certain extent. But I think Apple’s taking back a lot of that control with iOS 14.

iOS 14 still allows freemium and free-to-play—and I think the free-to-play isn’t a problem in and of itself—what Apple is really curbing is the unintended consequences of the free-to-play really exploding.

David: Yeah, that is a good point too, and again, this is why I’m really bullish on subscriptions. Two of my apps are subscriptions. And it was in installing subscriptions into my app—that was just a mess—is why I ended up at RevenueCat. And then now, not only do I get to run my subscription app business personally, but then I get to, as a developer advocate, to work with all these developers.

We’re working on a podcast, a community of subscription app developers and things like that. And so I’m just so inundated in this. So you can take all this with a huge grain of salt. But why I’m so bullish about subscriptions, is that it does realign incentives. So if you set aside the apps that get really good at tricking people into subscribing and finding the users who forget to unsubscribe—that is definitely a part of the market and it’s the part that I personally hope suffers in the coming years. But if you put that aside, most subscription apps are very directly aligned with creating value for users.

A great example of this, which I use, is VSCO, the photo editing app. When they first moved to subscription, I was like: “Hmm. 20 bucks a year? Alright, I’ll do it.” And I’m a happy subscriber. I only use the app a few times a month—I don’t use it every day. They’re not incentivized to send me a push notification every 24 hours and get me back in the app. Their incentive is to just build a great tool and make sure that user experience for me is so awesome. When I do want to edit a photo, I’ve got the presets I love. They’ve got a tonne of great features for editing that I’ve gotten used to using. And so if they can just continue delivering that value to me, I might be a VSCO subscriber for 10 years. And at 20 bucks a year a $200 lifetime value for me? That’s incredible. And guess what, I’m actually pretty happy to pay it, because I love the app. And it brings value to me.

So the people talking about subscription fatigue, worried that if every app moved to subscriptions, consumers are going to revolt. I think what’s missing there is the analysis of what people are actually going to pay for. You will have people who grudgingly subscribe to an app that they don’t really love or care about, just because they need a tool. But predominantly what you’re seeing is that consumers are subscribing to things they care about, and they’re willing to pay because these apps are bringing value in a way that hasn’t been available and hasn’t been practical for developers to build, given previous monetization models.

So, for example, again, a RevenueCat customer and somebody I’ve gotten to talk to quite a bit over the last year, since joining, is FitnessAI. It is the perfect example. He went through Y-Combinator and raised money for a fitness app on which you spend $60 a year.

You spend $60 a session for a personal trainer; you spend $60 a month on a gym membership. And his app has really sophisticated machine learning around how to progress through sets, how to build programmes, and he had collected a tonne of that data from an app previously and then built FitnessAI on top of it. And the subscription business model aligns him with these users who are thrilled to pay 60 bucks a year, to enhance what they’re already spending 60 bucks a month at the gym.

And so what we’re going to see play out in the coming years is that there’s going to be all sorts of tools that get built, and not just tools, but entertainment experiences and other things, that delivered deep value to people. When you actually are delivering that level of value, the subscription model, and even the pricing, starts to become much more tenable to consumers.

Another great example is Flighty. It’s a friend of mine who built that app. It’s a flight tracking app, and it is phenomenal. And he couldn’t have built that without a subscription model. His data costs are insane, because flight data is really expensive. But because of the subscription model, he was able to build an incredible tool for people who are flying all the time.

Guess what you’re paying $300-600 a flight. And he charges $60-80 a year. So $60-80 a year to have this sophisticated tool in your pocket that tells you where your plane is, at any time; if it’s going to be running late; what your gate is going to be; you land and it sends you a notification of where to pick up your bags; and what the weather is; and how to get to the Uber.

These kinds of tools are just going to continue to enhance our lives and add value. And being able to charge users for that value is the key to being able to build that stuff. And so it really is maybe the biggest fundamental change to incentives alignment that we’ve ever seen in mobile app businesses. And I think we’re just in the early phases of that. I think we’re going to see just entirely new classes of apps that come out.

I’m actually really bullish too for, not just B2C apps, but B2B apps. I think over the next 5-10 years, we’re gonna see mobile-first B2B solutions. Everybody’s doing more and more work, remote and on the go. And so you kind of see that already with certain apps that are more business-focused, and I think we’re going to see more and more of that. So yeah, I think we’re in the early innings of a very long game. That’s pretty exciting to be involved in.

Shamanth: Definitely, definitely. I like how you phrase it as an incentive realignment. Certainly, I think subscriptions have allowed a whole new category and class of apps to flourish. And I also like the example you gave earlier on about the knitting app, which couldn’t have flourished as a free-to-play app at all. It would be very challenging for them, if they have to have consumables, or being a one-time paid app; that neither of those models would have worked. But I personally like to look at these as micro utilities, which is that these are utilities for a specific niche of the population, like the flight tracker app and knitting app. I know you mentioned, the last time we spoke, a fishing app.

David: Yeah.

Shamanth: For a certain category of people, that is something they would use daily or weekly. And that’s all the app needs to flourish. And it sounds like the system’s incentives is enabling that to happen, rather than just free-to-play, mass market apps, which again, are healthy and have their place. But I think there’s a complete realignment of how the app economy is going to evolve.

David: Yeah, and I think important to that as well is a realignment of consumer spending. So people are like: “Oh, wow, I’m gonna have to subscribe to that?”, “I’ve got to pay for software?”, “Subscriptions suck!” and you hear all this negative, negative, negative negative from certain people. Especially since I’m more in the indie developer scene on Twitter, and there’s just a lot of BS floating around.

But I think what we’re seeing is the younger generation who is raised on software; they’re used to software providing value in their life, even more so than me as a Gen Xer. I’m 41 years old. I had a Nintendo Entertainment System and a Commodore 64. And software didn’t really start delivering much value in my life until late high school, college and even after that. And so my perspective and propensity to spend is higher compared to previous generations, but lower compared to the generations coming who are used to digital experiences enhancing their life and adding value.

If you think about consumer spending more broadly, and you have somebody who goes out to eat a lot; they’re spending $60-80-100-200. Or a foodie going to fine restaurants, maybe spending $200-300 a meal on these experiences, because it brings value, they enjoy them. If there’s a foodie app that contributed to that experience, and alerted you to the next hot restaurant and a community of foodies that you could talk to for $60 a year?

I don’t even think we’re seeing the threshold of what you’re going to be able to charge for some of these apps. What we’re seeing $60-80-100 a year is just a start. I think that you’re going to have niches, and value created through these mobile experiences that are going to bring so much value that paying $200 a year for a foodie app, when you’re spending $200 a meal on your in-person experiences—if you can find ways to add value to those experiences, then pricing is going to look a lot different. And then you have apps like Tinder just crushing it.

And what’s really fascinating to me about Tinder is that, not only are they using the subscription model, but they have consumable purchases in there.

I think we’re also at the beginning stages of subscription apps figuring out how to better monetize the true fans, who would excitedly spend hundreds of dollars a year in the app, not just a $20 a year subscription. And I think we’re going to see that more and more. And you’ve already seen that shift in the last probably 5-10 years.

Taylor Swift, when she releases an album, releases all these special editions that are hundreds of dollars. Radiohead famously did things like that as well. And most artists do that, with merchandise and finding other ways to monetize to where a hardcore Taylor Swift Fan, who just loves that experience and loves her music and loves the persona, may be spending thousands of dollars a year on a combination of merchandise and premium albums. Some of these artists are creating their own apps now that are subscription apps, like their own communities.

So I think we’re at the very early stages of really exploring how much value mobile devices can bring to our lives. And it’s kind of funny to say that in 2020; it’s, well, obvious. It’s obvious that the iPhone brings a tonne of value. Everybody has a mobile device now, and of course, they bring a lot of value. And then of course, there’s a lot of negatives with screen addiction and things like that.

But I really think we’re still in the early days of figuring out what that’s really going to look like in the coming decades, in part because we haven’t had the monetization and the incentives alignment that we’re starting to see now with subscriptions, the freemium business model, and other things starting to come together. And so I think we’re in the early stages of the next phase of mobile.

Shamanth: Certainly, David. This has been a wide-ranging conversation. Certainly, it’s one that fills me with optimism and hope for what’s coming for the app economy. Certainly, there’s some amount of uncertainty in the short term. There’s definitely a lot of hope for what’s coming the long term for us. This perhaps is a good place for us to start to wrap, David. But before we do that, can you tell folks how they can find out more about you and everything you do?

David: Sure. Embarrassingly, you can follow me on Twitter. I rant—I try to not get too much into politics and things like that—but I’ll rant on Apple and complain about what their latest gimmicks are. As I said, I didn’t really get into it much, but I am a developer advocate at RevenueCat.

So keep an eye on the RevenueCat blog for more of this kind of thoughts on the future of subscriptions, the future of the app economy. And then also as part of my job at RevenueCat, I’m launching a podcast called Sub Club.

Shamanth: We’ll link to all of that in the show notes.

David: Yeah. So I guess that’s about it.

Shamanth: Excellent. Yeah, David, thank you so much, again, for sharing your wisdom. And I know, this has been 12 years of your experience. And I really do appreciate how you distilled all of your wisdom. Especially I think I value this so much because knowing and understanding where we came from, and to be better informed about where we’re going. And certainly, a lot of the impact of past decisions has been very interesting and fascinating for me to know and understand through our conversation today. So thank you so much for being on the Mobile User Acquisition Show.

David: Thanks for having me.

A REQUEST BEFORE YOU GO

I have a very important favor to ask, which as those of you who know me know I don’t do often. If you get any pleasure or inspiration from this episode, could you PLEASE leave a review on your favorite podcasting platform – be it iTunes, Overcast, Spotify, Google Podcasts or wherever you get your podcast fix. This podcast is very much a labor of love – and each episode takes many many hours to put together. When you write a review, it will not only be a great deal of encouragement to us, but it will also support getting the word out about the Mobile User Acquisition Show.

Constructive criticism and suggestions for improvement are welcome, whether on podcasting platforms – or by email to shamanth at rocketshiphq.com. We read all reviews & I want to make this podcast better.

Thank you – and I look forward to seeing you with the next episode!